Borris Lace, Everyday Living Heritage

By Samantha Morris, PhD Candidate, TU Dublin

In Borris, a small village in southeast Ireland, a rich tradition of lacemaking continues not as a relic of the past, but as a living, evolving practice sustained through weekly workshops and community care. Known as Borris Lace, this heritage craft originated in the 1840s as a response to the profound social and economic upheaval of the Great Famine. Today, the ongoing practice of Borris Lace shows how knowledge, labour, and memory endure and adapt through hands-on engagement (Smith, 2006; Hafstein, 2018).

As a cultural heritage researcher, I take Borris Lace as a case study to explore how traditional craft practices contribute to the cultural and emotional meanings of place (Cresswell, 2015; Massey, 2005). Rather than viewing lace as a static artefact, I understand lacemaking as a form of living heritage (Adell et al., 2015; Kisić, 2016), one that actively shapes relationships, identity and belonging. This perspective draws on ethnographic methods (Pink, 2009; Grasseni, 2007; Ingold, 2013), interviews, archival research and participant observation to uncover how the tradition continues to evolve and what it means to those who sustain it.

Fig. 1. Borris Lacemakers logo

Borris Lace History

Borris Lace began during the Great Famine as a philanthropic cottage industry aimed at supporting local women and their families (Laurie & Meldrum, 2022). It provided a way for women to earn an income from home, allowing them to balance childcare and domestic responsibilities while contributing economically (Parker, 2010; Luckman, 2015). Amid widespread hardship, this textile work brought both material support and a sense of dignity.

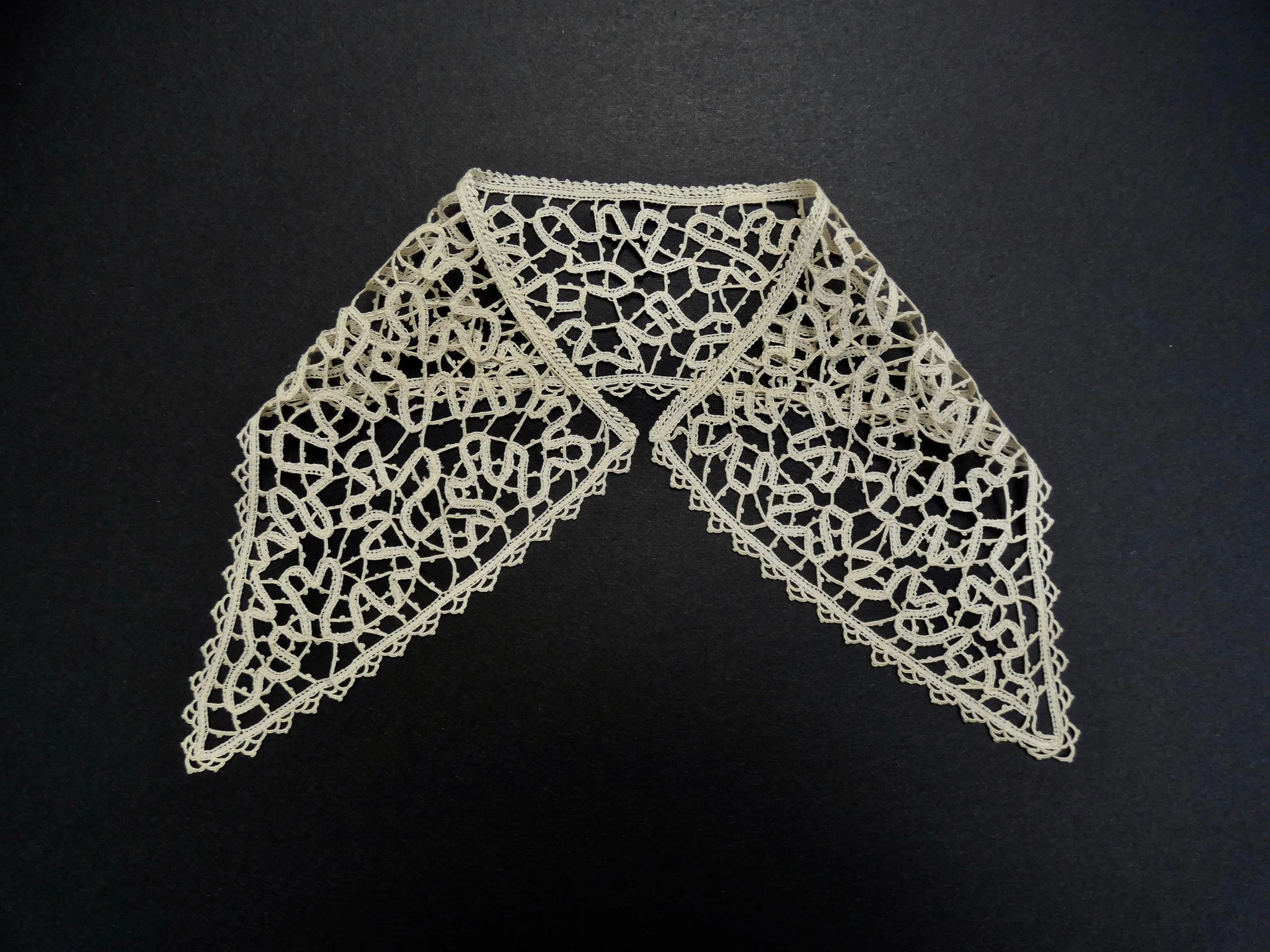

The lace itself is characterised by continuous flowing lines and botanical motifs. Like other Irish lace traditions such as Carrickmacross and Kenmare, Borris Lace emerged from a fusion of imported techniques and local adaptation (Ó Cléirigh & Rowe, 1995; Potter & Hayes, 2014). Its small-scale production and close community roots set it apart, making it a distinctive thread in the broader story of Irish craft heritage.

Fig. 2. Borris lace based on holly leaves. Photo: Borris Lacemakers.

Fig. 3. Example of Borris lace.

A Contemporary Revival

The tradition declined after the First World War due to rising costs, labour shortages and competition from cheaper machine-made lace (Potter & Hayes, 2014). While efforts in the 1990s attempted to revive the practice through classes and workshops, these were short-lived. In 2016, a more lasting revival began when Australian lacemaker Marie Laurie, working with the Borris House lace collection, started offering workshops in the local community (Laurie & Meldrum, 2022). These quickly gained popularity and the Borris Lacemakers group was formed. This community group now plays a central role in sustaining and teaching the craft, keeping local traditions alive through intergenerational learning and cultural participation (Ingold, 2013; Grasseni, 2007).

Fig. 4. Borris lacemaking.

Craft, Care and Women’s Work

Lacemaking, like many textile arts, has long been seen as women’s work, tied to the home and often treated as less important than other kinds of labour (Parker, 2010; Luckman, 2015). As a result, it has often been excluded from mainstream heritage narratives, which tend to focus on monuments, museums and formal institutions (Smith, 2006).

In Borris, makers speak of how the craft requires focus, patience and care. They describe feelings of calm, connection and memory associated with the act of stitching. These are forms of embodied knowledge that do not always fit into official categories of heritage but are vital for cultural continuity and wellbeing (Sennett, 2008; Pink, 2009).

Recent research in critical heritage studies urges greater attention to these everyday, emotional and domestic forms of heritage (Smith, 2006; Hafstein, 2018). International conventions now increasingly recognise intangible cultural heritage, including the transmission of traditional skills, memory and community values (UNESCO, n.d.). Borris Lace exemplifies these living dimensions, where meaning is sustained through relationships as much as through objects (Ahmed, 2004).

Fig. 5. Examples of Borris lace displayed as part of Ireland’s National Heritage Week 2022. Photo: Borris Lacemakers.

The Meanings of Place

The revival of Borris Lace is deeply tied to place. But place here is not simply a geographic location. It is made through memory, relationships and shared practice (Cresswell, 2015; Massey, 2005). As people gather to make lace, they also weave together stories, skills and a sense of belonging.

Many of the lace designs are named after local plants and rural landscapes (Laurie & Meldrum, 2022). A “lace garden” at Borris House brings some of these motifs into the landscape itself, linking craft and the environment in visible, creative ways. Such projects ground intangible traditions in the physical world, deepening connections between material culture and local identity (Ahmed, 2004; Adell et al., 2015). These initiatives also contribute to cultural tourism and rural regeneration (Luckman, 2015).

Fig. 6. Examples of Borris lace displayed. Photo: Borris Lacemakers.

Living Heritage

Borris Lace is not about preserving the past in a glass case. It is about supporting an evolving tradition that continues to matter today (Hafstein, 2018; Kisić, 2016). What is being passed on is not just a set of stitches, but a way of relating to each other, to history and to place (Ingold, 2013; Pink, 2009).

This challenges dominant heritage models that rely on expert authority, museum collections or static definitions of value (Smith, 2006). Instead, it calls for recognition of everyday creativity, shared knowledge and minor histories (Ahmed, 2004; Massey, 2005). The value of Borris Lace lies not only in the lace itself, but in the social fabric it helps to sustain.

By attending to this small, rural and previously marginalised tradition, we begin to see heritage as something lived and participatory, not owned but shared (Adell et al., 2015). What is made in Borris is not only lace, but a space where cultural meaning is negotiated through care, community and craft (Sennett, 2008; Grasseni, 2007).

Fig. 7. Examples of Borris Lace displayed as part of Ireland's National Heriatge Week 2023. Photo: Borris Lacemakers.

Further Information

More information on Borris Lace can be found The Irish History Students Podcast https://open.spotify.com/episode/3nwRbGyOkDaOADtUXMHiXP?si=sRtSpCNlTc2JsXX2lCSEBQ

And https://www.facebook.com/borrislace/

Further Reading

If you’d like to explore some of the ideas behind Borris Lace, heritage, and traditional craft in more depth, here are a few recommended reads that connect practice, place, and living cultural traditions.

Craft, Embodiment & Gendered Knowledge

Adamson, G., 2007. Thinking through craft. Oxford: Berg.

Luckman, S., 2015. Craft and the creative economy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Parker, R., 2010. The subversive stitch: Embroidery and the making of the feminine. 2nd ed. London: I.B. Tauris.

Sennett, R., 2008. The craftsman. London: Penguin Books.

Living Heritage & Critical Heritage Studies

Adell, N., Bendix, R., Bortolotto, C. and Tauschek, M., eds., 2015. Between imagined communities and communities of practice: Participation, territory and the making of heritage. Göttingen: Göttingen University Press.

Hafstein, V.T., 2018. Making intangible heritage: El Condor Pasa and other stories from UNESCO. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Kisić, V., 2016. Governing heritage dissonance: Promises and realities of Europe's cultural policies. Amsterdam: European Cultural Foundation / Amsterdam University Press.

Smith, L., 2006. Uses of heritage. London: Routledge.

Embodied Learning & Sensorial Knowledge

Grasseni, C., 2007. Skilled visions: Between apprenticeship and improvisation. New York: Berghahn Books.

Ingold, T., 2013. Making: Anthropology, archaeology, art and architecture. London: Routledge.

Pink, S., 2009. Doing sensory ethnography. London: SAGE Publications.

Place, Emotion & Cultural Geography

Ahmed, S., 2004. The cultural politics of emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Cresswell, T., 2015. Place: An introduction. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Massey, D., 2005. For space. London: SAGE Publications.

Irish Lace

Laurie, M. and Meldrum, A., 2022. The Borris Lace Collection: A unique Irish needle lace. Borris: Borris Lace Collection.

Ó Cléirigh, N. and Rowe, V., 1995. Limerick lace: A social history and a maker’s manual. Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe.

Potter, M. and Hayes, J., 2014. Amazing lace: A history of the Limerick lace industry. Limerick: Limerick City & County Council.

UNESCO, n.d. Intangible cultural heritage list. [online] Available at: https://ich.unesco.org [Accessed 1 Aug. 2025].